The ailments

In no particular order - alphabetical, chronological or otherwise - during my stay in hospital, I have suffered from:

Lymphoma (obviously)

Gout - in one toe

Diarrhoea & vomiting

Granuloma Annular - a red, harmless rash that spread across my face and upper body

Septicaemia

Deafness (partial, in one ear)

Ear infection

DVT (blood clot) in arm

Infection in arm

Alopecia (loss of hair)

Neutropenia (very low white blood cell/neutrophil count)

Hallucinations

Cognitive impairment

Chronic nosebleeds

(Mouth) thrush

Mouth ulcers

Haemorrhoids (piles)

Norovirus

Conjunctivitis

Common Cold

Many are directly as a result of chemotherapy and are know side effects like the loss of hair - often regarded as the 'signature' symptom of chemo and, indeed, cancer; cognitive impairment (often referred to as chemo-brain or chemo-fog) and mouth ulcers. Others, like gout, piles, rashes and - in particular for me - deafness, can be knock-on side effects of chemo. They don't happen to everyone and are not inevitable by any means. But chemo hits the body very hard - it is designed to in order to successfully attack and destroy cancer cells - and the effects of doing so, and destroying the body's immune system, can lead to all sorts of other problems.

Some can be anticipated and dealt with almost before they happen, for instance vomiting; chemo makes you sick and they give you anti-sickness pills as a matter of course as soon as you start. Likewise many infections can be headed off by the use of preventative antibiotics and because the whole system is tried and tested - unless you happen to be on a new, experimental drug for instance - many side effects and infectious problems can be dealt with even before they happen.

Take each day as it comes

As far as medical problems are concerned, many are inevitable and your medical team can talk you through what is happening to you, why and what they are doing to alleviate them. The best thing is to go with the flow; take each day as it comes as neither hospitals nor illnesses respond well to being rushed. Put plans on hold whilst you cope with this. There will be enough going on in your life without having to worry about what's going on at work with that important contract or how you are going to get the dog to the vet for a booster.

|

| Hair loss is fairly inevitable, but it does grow back |

Hair loss is probably one of the obvious ones - much easier for an ill bloke to deal with than an ill woman. A good friend who lost her hair was very distressed about it and the cold head treatment to help prevent it was equally unpleasant. From my point of view, it was just one of those things that was going to happen so I had my hair cut very short to start with. To my wife's dismay I never did lose my eyebrows. Not having to shave for a while I regarded as a bonus. Hair grows back after treatment has finished.

Physical problems - food

Loss of taste, loss of appetite, mouth ulcers, feeling sick and hospital food: what a combination. Regarding loss of taste, it is short-lived for the few days when you are neutropenic; it's not nice but not a lot worse than losing your sense of flavour when you have a bad cold. I found that sweet things were less affected than savoury; so for a few days I lived on syrup sponge (or similar) and custard. Don't be tempted to try the tikka masala - all that happens is it hurts any mouth ulcers you might have, still tastes of cardboard but is red hot into the bargain. Sweet and sour chicken is better. Some days you may not feel like eating at all - this is quite understandable. Don't force it down, just over-compensate when you do feel like eating and don't worry about snacking/grazing. This is your perfect excuse to demolish the odd Snicker or Crunchie with a clear conscience. You must eat - being ill actually uses a lot of calories - and although you should avoid stuff like unpasteurised or processed dairy products, unwashed salad, under-cooked meat, shellfish, boiled/fried/poached eggs (the yolks are still basically uncooked) - don't worry about how many pounds you might put on, it's irrelevant. You'll lose more than you gain for sure. Make sure you use a mouth wash (that doesn't react with toothpaste) and rinse your mouth with saline washes frequently, especially when your mouth is sore. The medical staff can give you these.

I found sneaking in some simple foods not readily available in hospital made a huge difference - probably the biggest being brown sugar to have with porridge. White just doesn't do it for me. I also love beetroot with macaroni or cauliflower cheese and it's good for you too. Tomato ketchup isn't but it does make that 'all day breakfast' (which is available at Southampton General at any time except breakfast) go down a lot better.

|

| Not a standard hospital breakfast - but it can be |

Finally if you are in for a long haul, ask to see a dietician and she/he can outline a supplementary menu for you and arrange for you to have stuff that isn't on the normal menu - like a decent fish and chips or cottage pie.

Physical problems - drink

Chemo can play havoc with your kidneys and renal system so drink plenty of water or squash and keep the system flushing well throughout your treatment. This is very important. At times, you will have bags and bags of intravenous fluids added to your chemo or before/after it, and this will pile on the pounds in fluid - at which point they will give you a diuretic to get rid of it all again. But it's like a toilet cistern - the more it's used, the better it will work. It is probably true that most of us don't drink enough water every day, even when we are well. So take heed and slosh it down. Squash helps. Many trips to the loo required but worth it.

Physical problems - fatigue

Fatigue is not just feeling long-walk-tired. It is an inability to function physically and mentally and is probably what ME sufferers endure but find so difficult to explain. Some days you will just want to close your eyes and let the day wash over you. So let it, don't force it. There will be good days, there will be not so good and (remembering to take each day as it comes) don't push yourself or get annoyed if you can't concentrate on that crossword or book, or you just feel like dozing all day. That's ok, it's your illness, your body and no-one should be hitting you with a deadline right now. Often it comes at the same time as nausea so eyes closed/headphones on is good for both.

|

| Cannulas - uncomfortable and impractical |

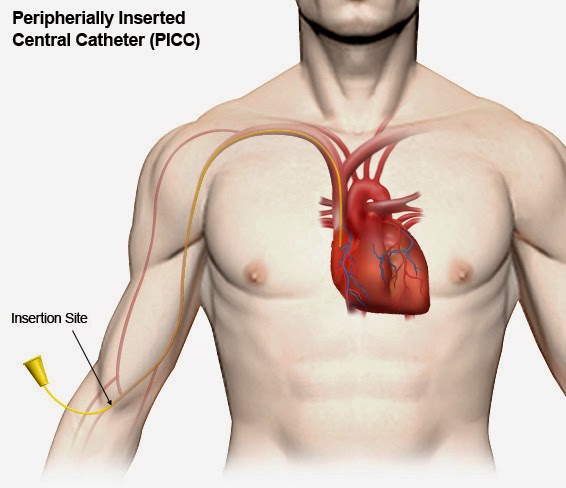

If you are in for a while, cannulas (needles) in your arms/hands are uncomfortable, impractical and inefficient. You will probably have a Hickman line inserted into your chest cavity (sounds worse than it is) or a PICC line in your arm. This allows for intravenous fluids, including chemo, antibiotics, blood, platelets and drugs to be administered quickly and easily, and bloods taken for testing through the same tube(s). Once in, they need looking after and dressing once a week. They shouldn't get too wet so I used clingfilm to keep mine dry in the shower before I managed to get a special waterproof protector prescribed for me (ironically not by the hospital but the district nurse). This is a brilliantly simple device which keeps the dressing dry.

|

| The Limbo waterproof dressing protector. Easier than clingfilm |

My first PICC line was mistreated a little and pulled out further than it should have done whilst the dressing was changed. This was dangerous as it meant the line was stopping short of the chest cavity and I ended up with a DVT, or clot, as a result. It also had to be taken out and a new one put in the other arm. Add to this an infection and a very swollen arm and you can understand why I looked after my new one - and made sure everyone else did too, expert medical staff or not. This was MY line and I had to put up with the problems incurred by mistreatment of it.

Physical problems - long term

My treatment was 12 weeks long, and with delays that became 16 weeks. That's a long time and the chances are you will feel awful for a good 25% of it. You steel yourself for these times because you expect them, but what is often overlooked is the long term effect of chemo. It is accumulative, so you might start by feeling great but gradually over time, it will wear you down and you have to accept that you will not run a marathon or ride the London to Brighton until the body has gradually recovered from the effects. However there is nothing wrong with gentle exercise and when you can, do. Ignore the lift, take the stairs. Go for a walk, even if only to the end of the corridor and back. Set yourself achievable targets and unless you simply can't drag yourself out of bed, do a little every day. It will get the endorphins moving and make you feel better physically as well as giving you a sense of achievement. Some long term effects stay with you for a very long time, I understand. The neutropenic feeling of 'pins and needles' in your finger tips and feet is one of them and it is a strange feeling.

Other hints and tips - routine

If you are used to a daily routine at home, being plunged into the relentless hospital environment is alien and often upsetting; the hospital operates 24/7 and at busy times you are, with the best will in the world, just another patient in Ward D3/Bay 1. Many wards are understaffed and they won't have time to spend nattering with you. Try to establish a routine - wash or shower every day (if possible - if not ask for help), get dressed during the day and change into bedclothes at night. Bring your home comforts eg a cosy blanket and a framed picture or two to make it feel homely. Try to establish a normality which you may not feel - in the long run it will help you feel more like the normal 'you'.

Other hints and tips - keeping in touch

If you are in hospital, who is fielding all the enquiries into your health? Can they cope with it? Can you cope with it? When I first found myself in Winchester after surgery I put up an innocent 'Thank you to my friends and family for your support' post on Facebook. It received 140-odd 'likes' but almost as many queries into why exactly I was there and what was happening to me. People took bets on whether it was a heart attack or a stroke. I realised very quickly that I was going to have to keep them informed, or someone else - Sally probably - would have to. Hence the blog; I'm not advocating that everyone should write a blog but I would advise you to keep notes - on your treatment, your thoughts, the journey. If nothing else it will help you separate one day from another and you may find it cathartic, as I have. Social media, if it is your thing, is a very useful way of staying in touch with friends and well-wishers; as is email, telephone and texting. It will help to keep people informed and off your back and as importantly, off the back of the person back in headquarters who is probably going through the mill just as you are.

Which brings us to visitors. There will be times when they shouldn't come - for instance when you are sans immune system and they have a sore throat. There will be other, borderline, cases when well-meaning visitors will just pitch up and you may feel unable to cope with them. Don't be afraid to say "No" and encourage your headquarters to say "No" too, if you feel unable to cope with seeing people and making small talk. If they don't understand, explain; if they get snotty, ignore them because they are just being selfish. Most people will understand if you are not up to having visitors and will leave you alone.

|

| A faintly ridiculous state of affairs in the 21st century |

In an age where your local Park & Ride bus offers free wifi and certainly all trains that go further than 30 miles from their starting point do the same it seems faintly ridiculous for a hospital not to offer free wifi access to the internet (even if it is locked down in some areas to avoid abuse or over-use). Indeed, most hospitals and NHS Trusts offer free wifi access as standard, especially to longer term patents who may require it carry on their businesses whilst receiving treatment. I was therefore astounded to find on arrival at Southampton, that there was no access to the internet other than through standard 3G or the ridiculous contracted system they have in place in most of the hospital which involves an antiquated touch-screen monitor and a TV/phone/internet bundle that you need to take a mortgage out to pay for. This system is clunky, the screens are rubbish, the interface is poor and as far as value for money is concerned, don't get me started. There are a few, free services like outgoing telephone calls to landlines (beware - you pay through the nose for incoming), free radio (certain channels) and TV (five channels but only between 8am and midday) but the rest of it is a big con. A good book is much better value.

With a bit of encouragement and information from a friend I took the bold step to write to the CEO of Southampton General to explain that I was to be in hospital for the best part of 3-4 months and really could not exist without internet access to my own devices (not possible through the incumbent system). I was rewarded, for which I am grateful, by being granted access to one of the University routers. But I really shouldn't have had to do that and although I haven't passed that access code on to anyone or let on to many people about having my own personal access, I have been sorely tempted to make a big deal about it as it is ludicrous to (a) get locked into a silly contract and (b) deny what is these days deemed to be standard service.

So fight for it, and make a fuss, if you find yourself in this situation. It's bad enough being stuck in a hospital bed for weeks on end but if you are denied proper access to the outside world it becomes a problem on a whole different - and expensive - level. I for one relied on my phone texts, emails, social media and Skype to stay in touch.

Other hints and tips - ask!

This is your treatment and you are entitled to know what is going on. If you don't understand what is happening to you, ask. Ask to see your records. Query a decision if you think it unsound or you don't understand what they are doing; the clinical staff, for the most part, will know exactly what they are doing and why; the problem comes when it is not fully explained to you, so don't be afraid to ask. Remember who to ask though; the cleaning lady will not be in the best position to advise you on your treatment; the consultant will not take kindly to being asked to toast your bread or bring you a cup of Horlicks at night. The health assistants will be happy to make your bed, answer your buzzer and refer on, make that cup of Horlicks, weigh you and do obs. The nurses are the front line - they carry out the doctors' orders and advise back to them. They administer the drugs (including the chemo) and sort out the problems. Befriend them, they can be your staunchest allies. Don't hack them off or you'll get nowhere. Try and call them by their names, not 'Nurse' (especially if it's a Sister).

Other hints and tips - be patient

The staff are busy; you are one patient in many they are juggling to look after. So when they say "I'll put your antibiotic up at 3pm" don't be surprised if it happens until 4pm. Unless it is critical to you timing-wise (for instance you are having a procedure prior to going home and someone is waiting for you to finish), be patient - it will happen but when the staff are ready for you, not the other way around. But don't be afraid to gently remind (nag) if it gets ridiculous. Watch out for being promised something at 8am or 8pm when shifts change and handover instructions may get slightly lost.

Other hints and tips - going home

|

| Going home: waiting for your Discharge Letter and Meds |

"And how are you in yourself?"

The question still rings in my ears, along with the statement "you survive the treatment, you survive the cancer". There will be times when, however upbeat you might feel about your treatment and the eventual prognosis, you will hit the lows. Part of it may be psychosomatic: there is so much physical stuff going on and you are, after all, being poisoned deliberately it's no wonder that it can mess with your mood; part of it is being separated from your loved ones, concern for how they will cope in your absence, just how unfair it all is (why have I been singled out for this?); and some of it will be purely emotional. I was given gas and air for a bone marrow biopsy; one of the side effects of 'laughing gas' is to feel quite emotional and I ended up with tears running down my face for no apparent reason. I had another experience of this happening but without the gas and air. Emotional build-up is understandable and often it is difficult to talk to people about it. Remember that there are people there for you who can help - the Macmillan Nurses are fantastic and they offer (often on the hospital site) all sorts of help from a chat over a coffee to aromatherapies, reflexology, massage and other services. Make use of them - they are free and they know all about how to listen support you when you need help. The Lymphoma Association is another, more specific, organisation who offer help for free and with expertise in the subject. They can offer straightforward and easily digestible information on your particular type of lymphoma, too. The key is to remember that you are not on your own.